Breaking Barriers: Disney Legend Floyd Norman

Cartoonist. Storyman. Troublemaker. These are just a few of the words Floyd Norman may use to describe himself. Perhaps “perseverance" would best describe the life and career of this can-do artist, who has contributed to projects ranging from high art animation to Saturday Morning cartoons. Floyd has done a bit of everything, and he started it all at a time when the odds were stacked against him.

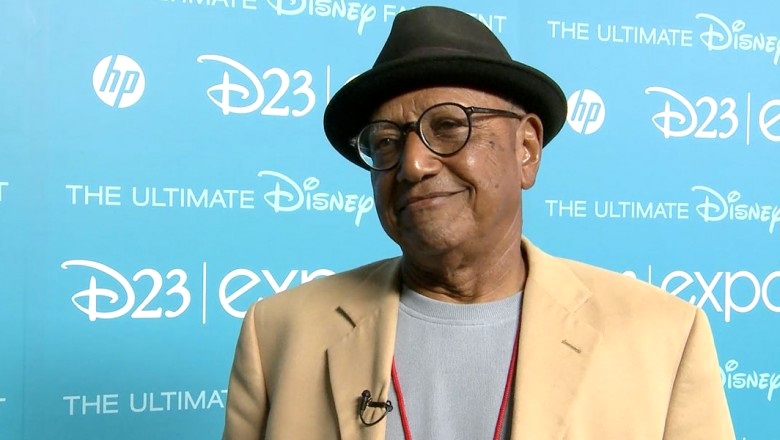

Image: D23

As part of our Disney Legends Spotlight series, let’s celebrate Floyd Norman - a legendary artist and self-proclaimed “troublemaker."

Aspirations in Animation

Floyd Norman was born June 22, 1935 in Santa Barbara, California. Growing up watching films like Dumbo and Bambi sparked his creativity, and he dreamed of one day working at Disney, helping to create stories like the ones he loved. Before he could even read, Floyd recognized Walt Disney’s iconic signature from the many books on which Walt put his stamp.

As a kid growing up in Southern California in the 1940s, Floyd would occasionally take trips to Los Angeles with his parents. One of those moments that would guide his career came from his dad, who would point out the “Mickey Mouse factory" in Burbank. Floyd knew where he wanted to be. He had stars in his eyes, and dreamed of one day joining the Disney Studio.

Santa Barbara treated Floyd very well. In fact, the place Floyd describes as a “Pacific Paradise" sheltered him from much of the racial tension and segregation of the time. Floyd admits "I didn't know it at the time, but my experience as a child was probably a good deal different from many, many people. We had access to everything — good schools, concert, theater." The idea of race as a limiting factor never even crossed Floyd’s mind.

Like many others in his area, Floyd attended Santa Barbara High School. Straight out of high school, Floyd took a stab at applying to Disney. He was rejected, but was offered words of encouragement to get some formal education, hone his craft, and come back again. Floyd’s grandmother - always a champion of his unique dreams and ambitions - got him enrolled in ArtCenter College of Design in nearby Pasadena, where he learned the art of illustration.

Floyd’s first break in illustration came under the guidance of comic artist Bill Woggon, creator of the Katy Keene comics. Under Woggon’s tutelage, Floyd performed some basic animation tasks like inking and painting. His early experience working with Woggon on serial comics taught Floyd how to tell stories with efficiency and humor - skills that would later define his animation style.

Breaking Barriers in the Disney Studios

In 1957, Floyd got his chance at Disney. As the first black artist ever to work in the Disney Studios long-term, Floyd started out as an assistant in-betweener. It was just about the lowest ranking artistic position within the studio, but it was a starting point for a career he would expand and enjoy for many decades. Floyd recalls the feeling he had when he started at Disney, musing “I wasn't even aware that I was an African-American. I was just another artist looking for a job." For Floyd, his goal was simply drawing and creating, not being defined by his race.

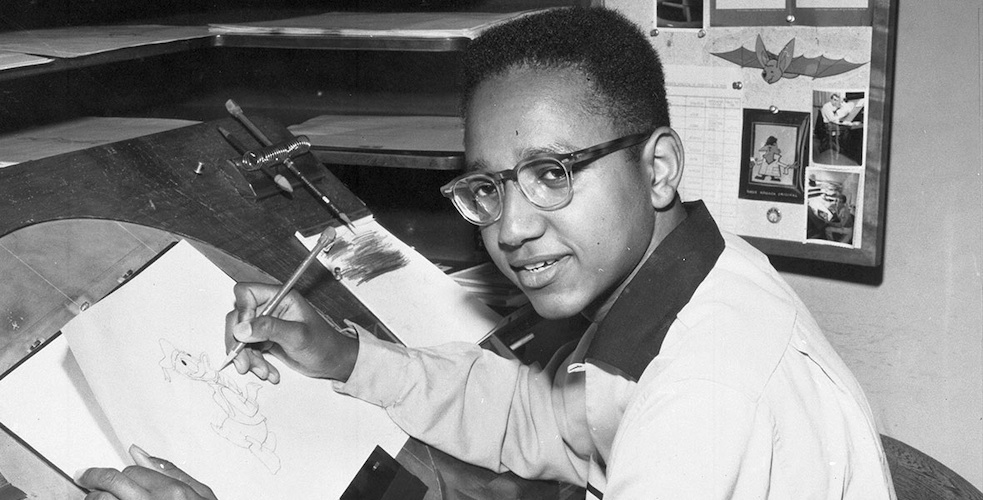

Image: Disney

To say Floyd’s first Disney project was a big one would be a massive understatement. He was invited to work on Sleeping Beauty - Disney’s most artistically ambitious animated film to date, as an in-betweener for the three fairies. Despite the challenges of being one of the only Black artists at the studio, Floyd quickly proved himself around the studio through dedication and talent.

The expression “Timing is everything" could not be more appropriate to describe Floyd’s entry into Disney. He began animation in the studio during the height of Walt’s “Nine Old Men" - the iconic group of artists who led Disney’s golden age of animation. During Floyd’s early years, the Nine Old Men were at their career peaks, and many were eyeing retirement. Floyd was a sponge, benefitting from the guidance of these titans of Disney animation, and forging friendships along the way.

One of the most unique members of Walt’s Nine Old Men was railroader enthusiast and jazz aficionado Ward Kimball, who was known for his eclectic fashion and frenetic personality. When the issue of race came up against Floyd among some folks working in the studio, Kimball was furious. He immediately went to bat for Floyd - something Floyd has always remembered and appreciated.

Following his work on Sleeping Beauty, Norman was drafted into the military and served a short period stint in 1960. When he returned to the studio, Floyd was spotted to animate on One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) and The Sword in the Stone (1963). Floyd’s pen was also put to action on animated sequences from Disney’s 1964 film Mary Poppins, as assistant animator.

Image: Disney

While keeping busy in animation, Floyd - like many artists at Disney - drew cartoons of his own as a means of self therapy. Floys contributed silly drawings of other animators and other employees around Disney just for fun. His humor got him noticed. Floyd was personally requested by Walt to work on the story for The Jungle Book (1967), where he worked with Disney Legend Woolie Reitherman and Walt himself. Floyd was principally responsible for storyboarding the sequences where Mowgli and Shere Khan mingle with Kaa the snake. After pitching the sequence to the boss, Walt said "that'll work," which in Walt’s lexicon meant high praise.

Unfortunately, Walt never lived to see the release of The Jungle Book, having died in 1966.

Blazing a New Trail

With the passing of Walt, Floyd decided he was ready for a new challenge. He left the Disney studio and teamed up with animator and director Leo Sullivan to co-found Vignette Films. As the first Black-owned animation production company, Vignette produced educational films about Black historical figures like George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington. Floyd and Sullivan chronicled the civil rights movement, filming riots in Los Angeles, contributing footage that made it to NBC. Through Vignette Films, Floyd and Sullivan creatively spread a positive message of love and unity.

But in addition to educational films, Vignette also worked on various Hollywood television projects, most notably the 1969 special Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert, which inspired a long running series Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids. Floyd and Sullivan worked in record time to animate the animated opening for the Soul Train series, and also wrote for sketch comedy series like Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In.

Image: Universal

Unfortunately, Vignette Films struggled to turn a profit. Floyd and Sullivan were evicted from their office space due to unpaid bills, and they worked out of a Hollywood coffee shop for a while trying to finish up projects. The company ultimately went bankrupt, and Floyd went back to Disney.

While working his second stint with Disney, Floyd worked on Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) and Robin Hood (1973), until Disney let him go for financial reasons.

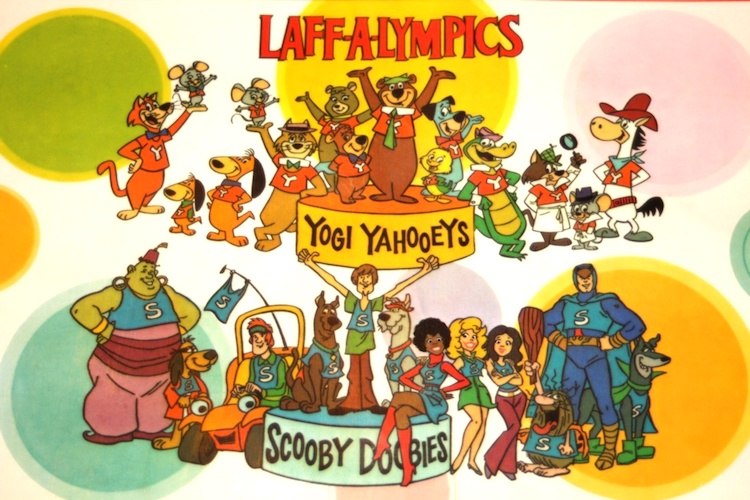

What happened next is the stuff of cartoon legend. Floyd Norman began working with Hanna-Barbera as a layout artist. He was soon approached by studio head William Barbera to write for some of the cartoons in production. Floyd embarked upon a prolific period of cartoon creativity, and his contributions to Hanna-Barbera’s catalog are a “Who’s Who" of Saturday Morning legends. Floyd worked on dozens of titles, including Kwicky Koala, Scooby Doo, Johnny Quest, Josie and the Pussycats, Smurfs, Laff-A-Lympics, Snorks, Captain Caveman, Super Friends, Ritchie Rich, and the list goes on. If you are old enough to have watched these cartoon classics, you surely saw Floyd Norman’s story writing and animation at work.

Image: Hanna-Barbera Productions

Modern Day Disney

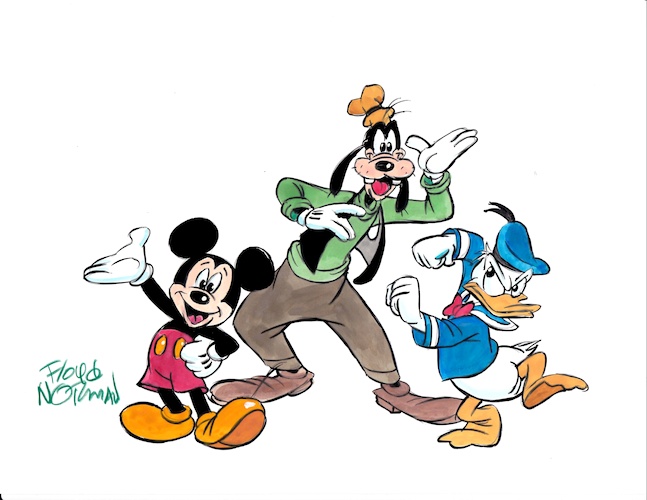

In the 1980s, Disney came calling for Floyd again, offering him a job as a writer for Mickey Mouse comics. Floyd produced six “dailies" and a Sunday comic for nearly 6 years, until Disney and King Features discontinued the strip, and Disney let Floyd go again.

Image: Floyd Norman

In what had become a continued pattern, Floyd wasn’t gone from Disney for very long. The studio sought his storytelling contributions on some big time projects in the 1990s, including The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) and Mulan (1998). In the 2000s, Floyd made contributions to The Tigger Movie (2000), Dinosaur (2000), and Kronk’s New Groove (2005).

But Floyd’s modern day Disney contributions aren’t just limited to the Walt Disney Studios. Floyd shared his decades of talent and wisdom with a new generation of artists at Pixar, contributing as a story artist to Toy Story 2 (1999) and Monsters, Inc. (2001). Floyd’s ability to keep current with new technologies, while maintaining his classical animation principles, allowed him to be a role model for younger artists entering the field of animation.

A Lifetime of Animated Inspiration

A lifetime of excellence in the field of animation has showered Floyd Norman with well-deserved recognition. Here are just a few of Floyd’s honors:

- Inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame (1979).

- Winsor McCay Award for "recognition of lifetime or career contributions to the art of animation" (2002).

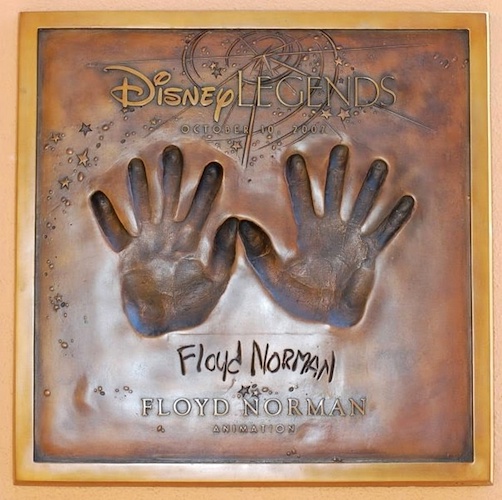

- Disney Legend award (2007).

- Friz Freleng Award for Lifetime Achievement for Excellence in Animation (2015).

- Special Achievement Award (Legendary Animator) from the African-American Film Critics Association (2016).

- Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Cartoonists Society (2019).

- Inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame (2021).

In His Own Words

Many pieces (like this one) have been written about Floyd Norman, but the master cartoonist has also written and published several books inspired by his lifetime of experiences in the animation, including the following:

- Faster! Cheaper!: The Flip Side to the Art of Animation

- Son of Faster, Cheaper!: A Sharp Look Inside the Animation Business

- How the Grinch Stole Disney

- Disk Drive: Animated Humor in the Digital Age

- Suspended Animation: The Art Form That Refuses To Die

- Animated Life: A Lifetime of Tips, Tricks, Techniques and Stories from an Animation Legend

Floyd is the subject of a 2016 documentary about himself titled Floyd Norman: An Animated Life, and has made appearances in many other documentary films about his animation experience and his time with the Walt Disney Company.

Floyd Norman - He Just Keeps Getting Better

Floyd Norman’s career in art and animation spans seven decades. Like a fine wine, Floyd’s talent and art get better with age. At 90 years young, Floyd continues to create fresh new pieces from his vast catalog (along with many other pieces, since Floyd can successfully draw pretty much anything he wants).

When Floyd strolls through the Disney Studio, he creates a buzz that draws artists in from around the campus. His gentle yet magnetic personality makes him instantly likeable, and also makes him an ideal ambassador for Walt Disney Animation.

Cartoonist. Storyman. Troublemaker. Disney Legend. This is Floyd Norman.

Offer a comment or share this article with a friend by reaching out on social at:

Check out more Disney Legends in our spotlight collection.

Sources:

Disney D23 Legend page - Floyd Norman

Floyd Norman: An Animated Life: Michael Fiore and Erik Sharkey, 2016